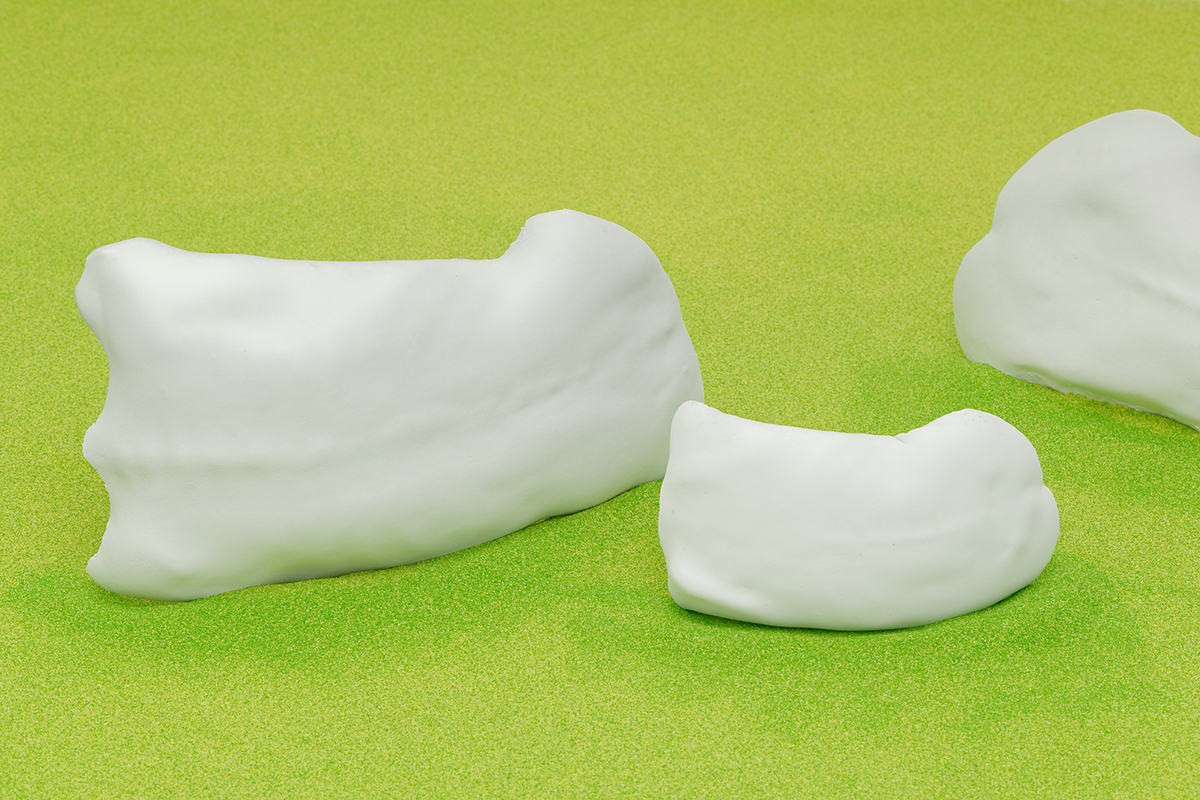

For her first major show in a French institution, Vanessa Billy presents an environment where human figures intermingle with representations of plant life, minerals, microbes and mechanical parts. These different elements are testament to her fascination with the interaction between humans and technology and the recycling and the transformation of forms of matter. Her most recent explorations seem to be leading her toward the production of objects that, to put it more precisely; interrogate the concept of transmutation and by extension nature’s epistemological limits. While her sculpture has an abstract and poetic dimension, it is deeply rooted in the physicality of her materials. This logic runs through this show whose “impressions de vies” is meant both literally and metaphorically. In her sculptural practice, an impression means to leave a mark, make an imprint, mark the effect of one body on another. The result of this process is a collection of casts that represent elements inspired more or less distinctly by the human body, set against more ambiguous moulds of other living organisms.

The ambivalence of these shapes demonstrates a kind of infinite transmutation of organisms and their interdependence with their milieu. A central piece in this show employs a cat’s cradle, the construction of simple figures using string wrapped around the hand of one or more players. This very basic technique makes it possible to invent an infinity of figures, ranging from the very simple to the highly complex. The biologist, philosopher and science fiction essayist Donna Haraway considers the game of cat’s cradle to be a possible model for reconsidering our place in and relationship with the world. Unlike evolutionist models, Haraway sees this practice as a way for players to link and knot paths that have consequences but are not determinist. The game is like a common process or journey, a communication between outstretched hands, in opposition to individualism and competition. Thus it becomes a logic of thought and action suggesting that we reconsider our relationship with the world from the viewpoint of improving the cohabitation and imbrication of different metabolisms.

With this assessment as her point of departure, Billy explores forms that highlight the metamorphoses of the human body, the mutations between animal and plant and between plant and the mechanical. Here the human is considered to be just one geological entity among others and to exist on the same plane as all other life forms. In the most literal sense she studies structures taken on by the living, the constraints of life being what confer different appearances to plants and minerals according to the functional demands of their environment. The concepts of the hybridization and transformation of energy are essential to her practice and she uses this as a way to break out of the dualism of nature and culture, and inscribe the human in a dehierarchized continuum. Her most recent works, devised for this exhibition, seek to give these ideas a tangible form.